Over the summer I defended my PhD thesis. You can find it here.

To give a super quick summary (prior to a rather verbose one ;)):

- Pre-2016 exploit generation was primarily focused on single-shot, completely automated exploits for stack-based buffer overflows in things like network daemons and file parsers. In my opinion, the architecture of such systems unlikely to enable exploit generation systems for more complex bug classes, different target software, and in the presence of mitigations.

- Inspired by the success of fuzzing at bug finding, I wanted to bring greybox input generation to bear on exploit generation. As a monolithic problem exploit generation is too complex a task for this to be feasible, so I set about breaking exploit generation down into phases and implementing greybox solutions for each stage. I designed these phases to be composable, and used a template language to enable for communication of solutions between phases.

- Composable solver solutions and a human-writable template language gives two, new, powerful capabilities for an exploit generation engine: 1) “Human in the loop” means we can automate the things that are currently automatable, while allowing a human to solve the things we don’t have good solvers for, and 2) If solutions are composable, and if a mock solution can be produced for any stage, then we can solve stages out of order. This leads to efficiency gains if a solution to one stage is expensive to produce, but we can mock it out and see if such a solution would even be useful to later stages, and then come back and solve for it if it does turn out to be useful. In practice I leveraged this to assume particular heap layouts, check if an exploit can be created from that point, and only come back and try to achieve that heap layout if it turns out to be exploitable.

- My belief is that the future of exploit generation systems will be architectures in which fuzzing-esque input generation mechanisms are applied to granular tasks within exploit generation, and the solutions to these problems are composed via template languages that allow for human provided solutions as necessary. Symbolic execution will play a limited, but important role, when precise reasoning is required, and other over-approximate static analysis will likely be used to narrow the search problems that both the input generation and symex engines have to consider.

- You’ll find a detailed description of the assumptions I’ve made in Chapter 1, as well as an outline of some of the most interesting future work, in my opinion, in the final chapter.

Background

I originally worked on exploit generation in 2009 (MSc thesis here), and the approach I developed was to use concolic execution to build SMT formulas representing path semantics for inputs that cause the program to crash, then conjoin these formulas with a logical condition expressing what a successful exploit would look like, and ask an SMT solver to figure out what inputs are required to produce the desired output. This works in some scenarios where there are limited protection mechanisms (IoT junk, for example), but has a number of limitations that prevent it from being a reasonable path to real-world automatic exploit generation (AEG) solutions. There’s the ever present issue with concolic execution that scaling it up to something like a web browser is a bit of an open problem, but the killer flaw is more conceptual, and it is worth explaining as it is the same flaw found at the heart of every exploit generation system I am aware of, right up to and including everything that participated in the DARPA Cyber Grand Challenge.

This earlier work (mine and others) essentially treats exploit generation as a two phase process. Firstly, they find a path to a location considered to be exploitable using a normal fuzzer or symbolic execution tool. ‘Exploitable’ almost always translates to ‘return address on the stack overwritten’ in this case, and this input is then passed to a second stage to convert it to an exploit. That second stage consists of rewriting the bytes in the original input that corrupt a function pointer or return address, and potentially also rewriting some other bytes to provide a payload that will execute a shell, or something similar. This rewriting is usually done by querying an SMT solver.

The conceptual flaw in this approach is the idea that a crashing input as discovered by a fuzzer will, in one step, be transformable into a functioning exploit. In reality, a crashing input from a fuzzer is usually just the starting point of a journey to produce an exploit, and more often than not the initial input leading to that crash is largely discarded once the bug has been manually triaged. The exploit developer will then begin to use it as part of a larger exploit that may involve multiple stages, and leverage the bug as one component piece.

Open Problems Circa 2016

From 2009 to 2016 I worked on other things, but in 2016 I decided to return to academia to do a PhD and picked up the topic again. Reviewing the systems that had participated in the DARPA CGC [3], as well as prior work, there were a few apparent interesting open problems and opportunities:

- All systems I found were focused on entirely automated exploit generation, with no capacity for tandem exploit generation with a human in the loop.

- No research I could find had yet to pick up on the notion of an ‘exploitation primitive’, which is fundamental in the manual construction of exploits, and will presumably be fundamental in any automated, or semi-automated approach.

- All systems treated AEG as essentially a two step process of 1) Find a path that triggers a bug, 2) Transform that path into an exploit in one shot, rather than a multi-stage ‘programming’ problem [4]. IMO, this is the primary limitation of these systems, as mentioned above, and the reason they are not extendable to more realistic scenarios.

- Nobody was really leveraging greybox input generation approaches (fuzzing) extensively, outside of the task of bug finding.

- Almost all systems were still focused on stack-based overflows.

- Nobody was working on integrating information leaks, or dealing with ASLR, in their exploit generation systems.

- Nobody was working on language interpreters/browsers.

- Nobody was working on kernels.

It’s likely that points 5-8 are the ‘reason’ for points 1-4. Once you decide to start tackling any of 5-8, by necessity, you must start thinking about multi-stage exploit generation, having human assistance, addressing bug classes other than stack-based overflows, and using greybox approaches in order to avoid the scalability traps in symbolic execution.

Research

With the above in mind (I didn’t touch 6 or 8), the primary goal for my PhD was to see if I could explore and validate some ideas that I think will push forward the state of the art, and form the foundation of AEG tools in the future. Those ideas are:

- Real exploits are often relatively complex programs, with multiple distinct phases in which different tasks must be solved. Much like with ‘normal’ program synthesis, it is likely that different tasks will require different solvers. Also, by breaking the problem down we naturally make it easier to solve as long as solutions to distinct phases are composable. Thus, my first goal was to break the exploitation process down into distinct phases, with the intention of implementing different solvers for each. An interesting side effect of breaking the exploit generation task down into multiple, distinct, phases was it allowed me to integrate the idea of ‘lazy’ resolution of these phases, and solve them out of order. In practice, what this meant was that if a solver for an early stage was much more expensive than a later stage then my system allowed one to ‘mock’ out a solution to the early stage, and only come back to solve it for real once it was validated that having a solution for it would actually lead to an exploit.

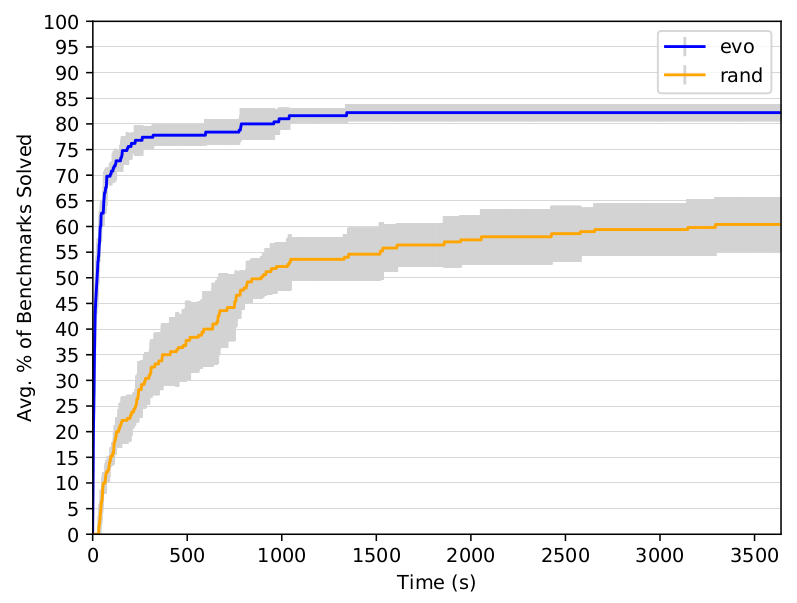

- Once exploit generation is broken down into multiple phases, we have decisions to make about how to solve each. Symbolic execution has powered the core of most exploit generation engines, but it has terrible performance characteristics. OTOH fuzzing has proven itself to be vastly more scalable and applicable to a larger set of programs. Why hadn’t fuzzing previously taken off as a primary component of of exploit generation? Well, if you treat exploit generation as a single, monolithic, problem then the state space is simply too large and there’s no reasonable feedback mechanism to navigate it. Greybox approaches that do input generation using mutation really need some sort of gradient to scale and a scoring mechanism to tell them how they are doing. Once we have broken the problem down into phases it becomes much easier to design feedback mechanisms for each stage, and the scale of the state space at each stage is also drastically reduced. My second goal was therefore to design purely greybox, fuzzing inspired, solutions for each phase of my exploitation pipeline. I purposefully committed to doing everything greybox to see how far I could push the idea, although in reality you would likely integrate an SMT solver for a few surgical tasks.

- I knew it would be unlikely I’d hit upon the best solver for each pipeline stage at a first attempt, and it’s even possible that a real solution for a particular pipeline stage might be an entire PhD’s worth of research in itself. Thus it is important to enable one to swap out a particular automated solution for either a human provided solution, or an alternate solver. My third goal was then to figure out a way to enable multiple solvers to interact, be swappable, and to allow for a human in the loop. To enable this I designed a template approach whereby each stage, and a human exploit developer, could write and update exploits in a template language that further stages could understand and process. I wrote about what this looks like in practice here.

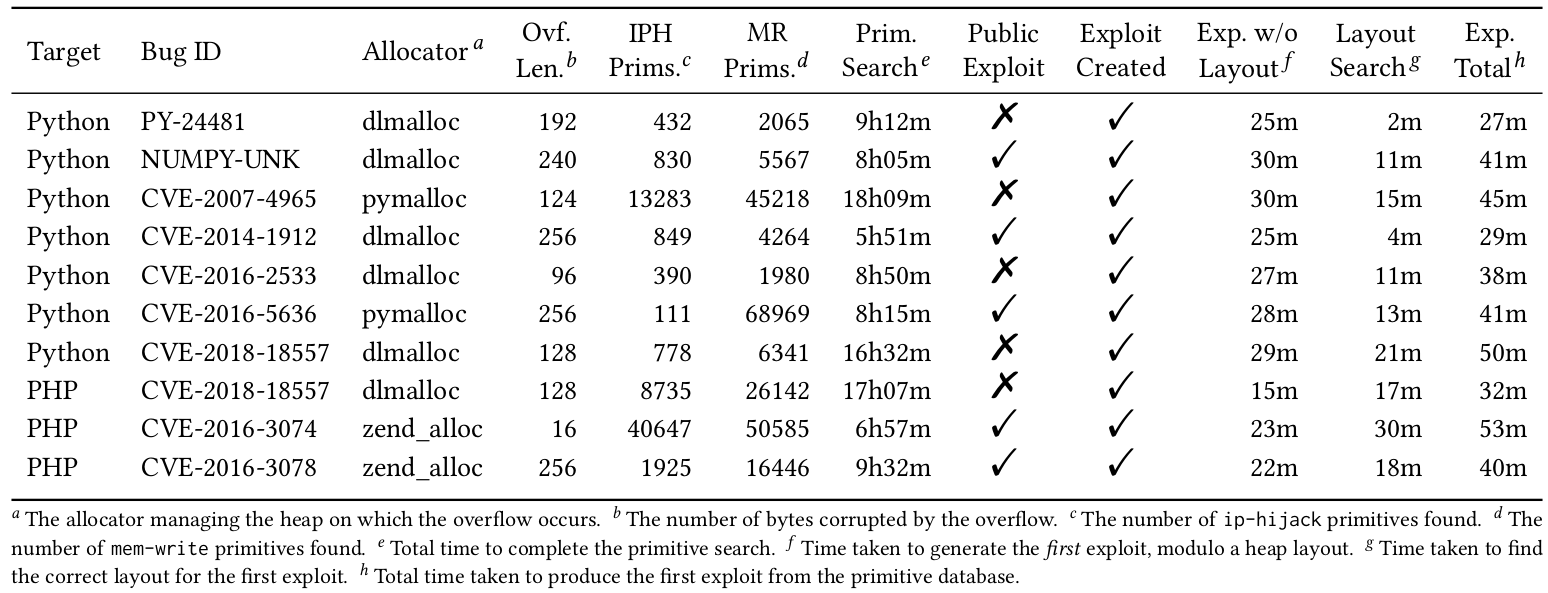

Alongside these goals I had to decide on a bug class and target software type to work with. Stack-based overflows had been done to death, so I decided to go with heap-based overflows which had received no attention. I also decided to target language interpreters (PHP and Python, in practice), as they’re ubiquitous and no exploit generation research had focused on them up to that point.

In the end the research was a lot of fun, and hopefully useful to others. I think the ideas of breaking down exploitation into multiple phases, using greybox solutions as much as possible, and using template-driven exploitation to integrate various solvers, or optionally a human, have real legs and are likely to be found in practical AEG engines of the future.

P.S. Thanks to my colleagues and friends that allowed me to bounce ideas off them, that read drafts, and that were generally awesome. Thanks as well to the anonymous reviewers of CCS, USENIX Security, and IEEE S&P. A lot of words have been written about the problems of the academic review process for both authors and reviewers, but on an individual and personal level I can’t but appreciate the fact that total strangers took their time to work through my papers and provide feedback.

Further Reading

Thesis – Contains all of my research, along with a lot of introductory and background material, as well as ideas for future work. One of the things I wanted to be quite clear about in my work was the limitations, and in those limitations it’s clear there’s plenty of scope for multiple more PhDs from this topic. In Section 1.2 I outline my assumptions, and by thinking about how to alleviate these you’ll find multiple interesting problems. In Section 6.1 I explicitly outline a bunch of open problems that are interesting to me. (Btw, if you do end up working on research in the area and would like feedback on anything feel free to drop me a mail).

Automatic Heap Layout Manipulation for Exploitation (USENIX Security 2018) – A paper on the heap layout problem, and a greybox solution for it. Also discusses exploit templates.

Gollum: Modular and Greybox Exploit Generation for Heap Overflows in Interpreters (ACM CCS 2019) – A paper on an end-to-end architecture for exploit generation using entirely greybox components.