A couple of months back while looking into a heap overflow in Chrome* I found myself poking around in the internals of TCMalloc. What I found there was pretty interesting. Perhaps the implementers have been watching Twitter and decided to take a proactive approach to security researchers moaning about the difficulties of modern heap exploitation. Maybe they just got caught up in making a blazing fast allocator and couldn’t bring themselves to slow it down with nasty things like integrity checks. Either way, TCMalloc provides a cosy environment for heap exploits to thrive and is worth fully exploring to discover the possibilities it provides.

At Infiltrate next weekend, Agustin Gianni and I will be discussing (among other things) TCMalloc from the point of view of exploitation. Essentially our research into TCMalloc wasn’t so much ‘research’ as it was vulnerability necromancy. In the name of speed TCMalloc has forsaken almost any type of sanity checks you might think of. There are annoyances of course but they are artefacts of the algorithms rather than coherent attempts to detect corruption and prevent exploitation. As a result we can revive a number of primitives from heap exploits past as well as some unique to TCMalloc.

Like most custom allocators, TCMalloc operates by requesting large chunks of memory from the operating system via mmap, sbrk or VirtualAlloc and then uses its own methods to manage these chunks on calls to malloc, free, new, delete etc. Agustin wrote a high level overview here and Google’s project page is also useful for gaining a general idea of its workings. In this post I’m not going to go into the exact details of how the memory is managed (come see our presentation for that!) but instead briefly discuss how thread local free lists function and one useful exploit primitive we gain from it.

ThreadCache FreeList allocation

The front end allocator for TCMalloc (with TC standing for ThreadCache) consists of kNumClasses** per-thread free lists for allocations of size < 32768. The FreeLists store chunks of the same size. The bucket sizes are generated in SizeMap::Init and allocations that don’t map directly to a bucket size are simply rounded up to the next size. For allocations larger than 32768 the front end allocator is the PageHeap which stores Spans (runs of contiguous pages) and is not thread specific. The following code shows the interface to the allocator through a call to malloc***.

3604 static ALWAYS_INLINE void* do_malloc(size_t size) {

3605 void* ret = NULL;

3606

...

3611 // The following call forces module initialization

3612 TCMalloc_ThreadCache* heap = TCMalloc_ThreadCache::GetCache();

...

3621 if (size > kMaxSize) {

3622 // Use page-level allocator

3623 SpinLockHolder h(&pageheap_lock);

3624 Span* span = pageheap->New(pages(size));

3625 if (span != NULL) {

3626 ret = SpanToMallocResult(span);

3627 }

3628 } else {

3629 // The common case, and also the simplest. This just pops the

3630 // size-appropriate freelist, afer replenishing it if it's empty.

3631 ret = CheckedMallocResult(heap->Allocate(size));

3632 }

...

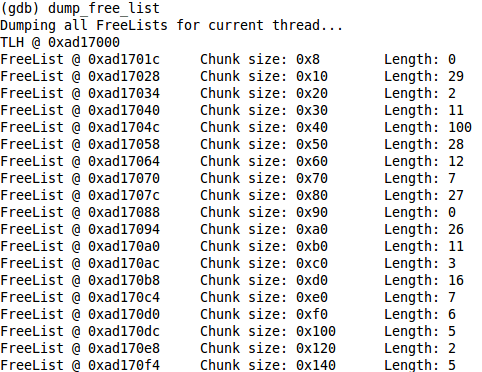

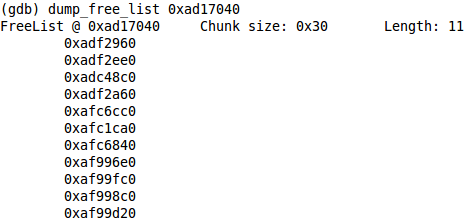

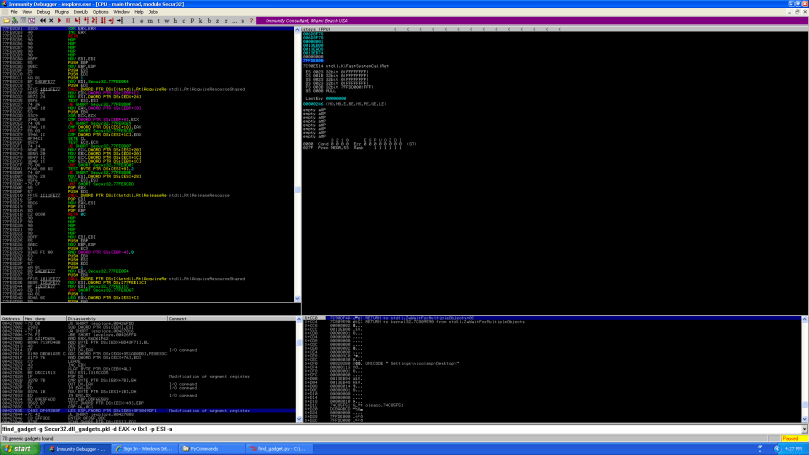

At line 3612 the ThreadCache pointer for the current thread is retrieved. This object contains a number of thread specific details but the one we are interested in is the FreeList array. A FreeList object contains some metadata and a singly-linked list of free chunks that are managed by very simple primitives such as SLL_Pop, SLL_Push etc. If the allocation size is less than 32768 then the following code is called to retrieve a chunk of the required size.

2888 ALWAYS_INLINE void* TCMalloc_ThreadCache::Allocate(size_t size) {

2889 ASSERT(size <= kMaxSize);

2890 const size_t cl = SizeClass(size);

2891 FreeList* list = &list_[cl];

2892 size_t allocationSize = ByteSizeForClass(cl);

2893 if (list->empty()) {

...

2896 }

2897 size_ -= allocationSize;

2898 return list->Pop();

2899 }

The correct FreeList is retrieved at line 2891 and presuming that it is not empty we retrieve a chunk by calling the Pop method. This results in a call to SLL_Pop with the address of the pointer to the head of the free list.

761 static inline void *SLL_Next(void *t) {

762 return *(reinterpret_cast(t));

763 }

...

774 static inline void *SLL_Pop(void **list) {

775 void *result = *list;

776 *list = SLL_Next(*list);

777 return result;

778 }

Insert to FreeList[X] – Reviving the 4-to-N byte Overflow Primitive

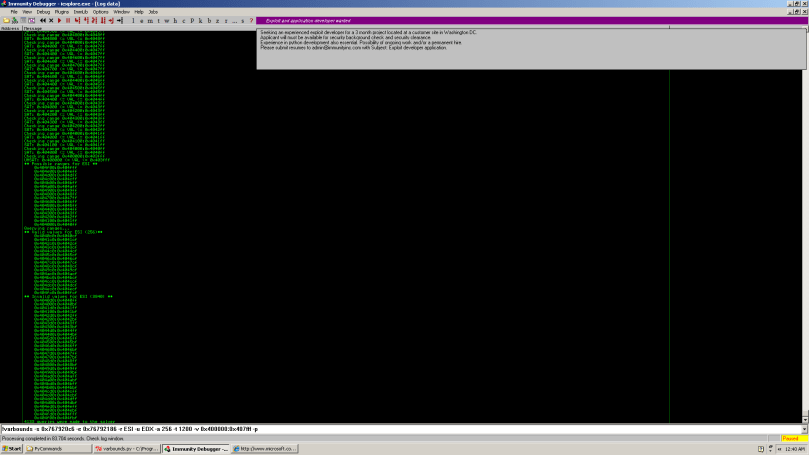

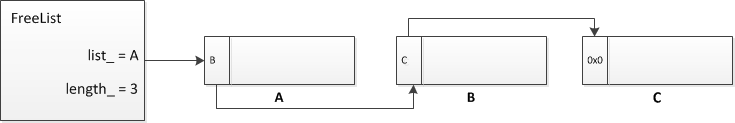

The effect of SLL_Pop is through SLL_Next to follow the list head pointer and retrieve the DWORD there and then make that the new list head. Notice there are no checks of any kind on the value of the *list pointer. When I first saw a crash within TCMalloc it was at line 762 in the SLL_Next function. The value of t was 0x41414141 which I had previously overflowed an allocated chunk with. What this means is that on that call to SLL_Pop the list head was an address that I controlled. How could this happen? Consider the following FreeList layout:

The above FreeList has 3 chunks. For simplicity assume that the addresses of A and B are contiguous****. On the first call to malloc chunk A is returned to the application.

Assume an overflow then occurs when the application writes data to A and B is partially corrupted.

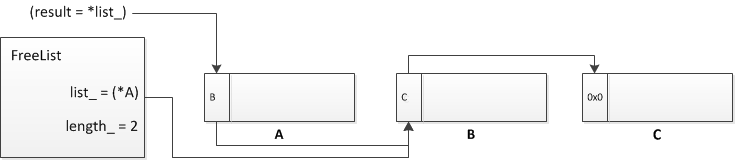

The first DWORD of B is the pointer to the next chunk in the FreeList and so we have corrupted the singly-linked list. The first chunk is now B and, as we control the first DWORD of this chunk, we control what the next chunk in the FreeList will be. The chunk C is effectively no longer part of the FreeList. The next allocation of this size will then return the chunk B (presuming no free calls on chunks of this size, within this thread, have occured. Free chunks are prepended to the head of the list) and it will give us control of the list head pointer when *list = SLL_Next(*list) executes.

As we control the DWORD at **list we control what the new list head is. In my initial TCMalloc crash this set the list head to 0x41414141. One more allocation of this size will then call SLL_Pop with a controlled list head pointer. The crash I encountered was when SLL_Next attempted to read the next pointer at 0x41414141.

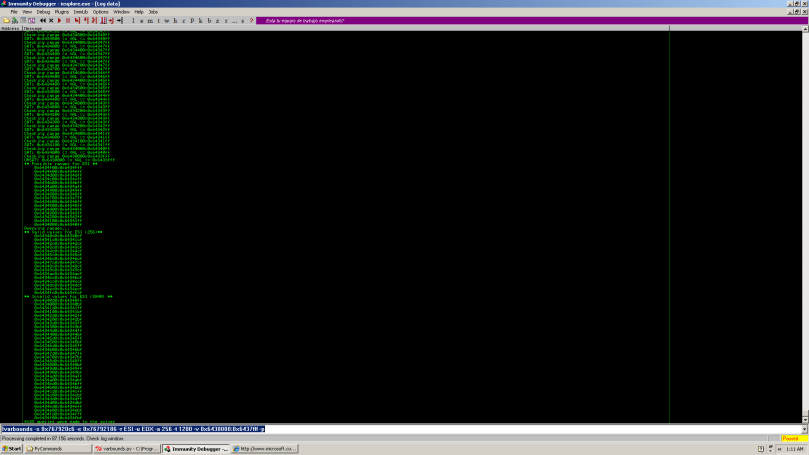

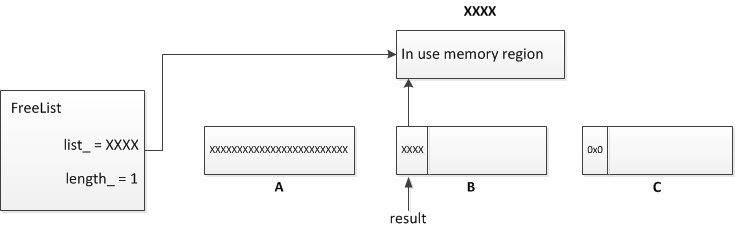

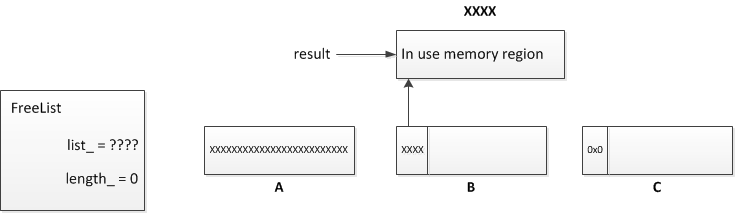

The important part of all this is that by controlling the list head pointer we control the address of the chunk returned and can give back any usable memory region we want to the application. So after one more allocation the situation is as follows:

The result of this allocation is a pointer which we control. It is important to note that the first DWORD at this address then becomes the new list head. For a clean exploit it is desirable for either this to be 0x0 or the FreeList list length_ attribute to be 0 after returning our controlled pointer. If we cannot force either of these conditions then future allocations of this size will follow this DWORD, which may not be under our control, and may result in instability in the program before we gain code execution. Another point to note is that if a free call occurs on a pointer that has not previously been noted by TCMalloc as part of a memory region under its control then it will raise an exception that will likely terminate the program. This is important to keep in mind if the memory location we are inserting into the free list is not controlled by TCMalloc. If this is the case then we have to prevent this address from being passed to free before we gain control of the programs execution.

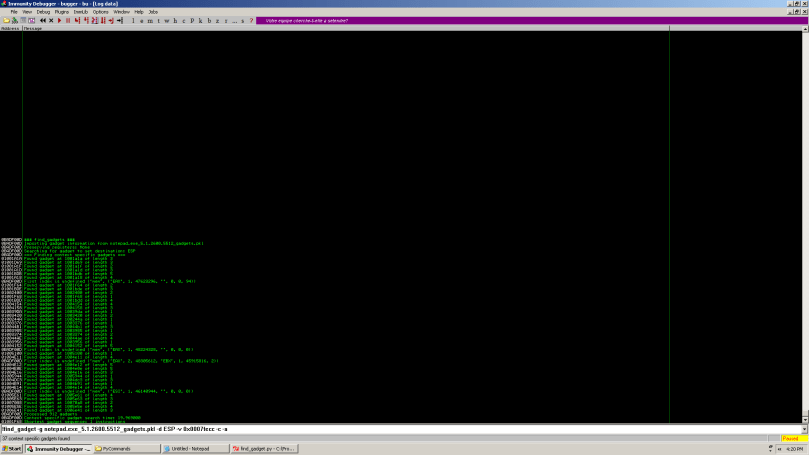

To gain code execution from this primitive it is necessary to find the address of some useful structure to hand back to the application and then have it overwrite that structure with data that we control. For modern systems this will require a memory leak of some kind to find such an address reliably (although heap spraying of useful objects might be an interesting alternative if we can write over one of these objects and then trigger a call through a function pointer or something similar). Despite this requirement, we have a functioning exploit primitive from a heap overflow and one that has not required us to deal with any heap integrity checks or protections. This is not a bad place to be in given the effort that has gone into securing the default allocators for most operating systems.The primitive basically gives the same effect as the Insert to Lookaside technique that was popular on Windows XP but has since been killed on Windows Vista and 7.

Conclusion

In this post I’ve given a quick overview of how we can convert a 4-byte overflow into one that overflows N bytes in an application using TCMalloc. This type of technique has been seen in various places in the past, most notably when overflowing chunks in the Windows XP Lookaside list. It has been largely killed elsewhere but due to the lack of integrity checks in TCMalloc it lives on in a relatively easy to use fashion.

At Infiltrate Agustin and I will discuss a variety of topics related to exploiting WebKit and TCMalloc in much greater detail. The Insert to FreeList[X] technique is but one example of a simple and old heap exploitation tactic that has been revived. Many other exploitation vectors exist and with a grasp of how the allocator works the possibilities are interesting and varied. In our presentation we will describe some of these techniques and also the details of how TCMalloc manages the processes of allocation and deallocation such as is relevant to manipulating the heap for exploitation.

* TCMalloc is not the allocator used by the Chrome Javascript engine V8. That has its own allocator that can be found in the src/v8/src/ directory of the Chrome source. Have a look at spaces.[cc|h] and platform_X.cc to get started.

** For WebKit in Safari kNumClasses is 68 but for Chrome it is 61. There seem to be some other differences between the various uses of TCMalloc and are worth keeping in mind. For example, in Chrome the maximum free list length is 8192 whereas in Safari is is 256.

*** We’re looking at the TCMalloc code embedded in WebKit revision 79746 Source/JavaScriptCore/wtf/FastMalloc.cpp. It’s effectively the same as that in the Chrome release and elsewhere, modulo the previous point.

**** FreeLists are created from Spans which are contiguous pages in memory that get subdivided to give the FreeList chunks. The chunks are prepended to the list during creation though so they end up in reverse address order. This means that if A, B are two contiguous addresses then the FreeList will initially be ordered as B -> A. In order to get the desired ordering we need to rearrange the fresh FreeList by allocating B, allocating A, free’ing B and then free’ing A. This will result in the ordering A -> B and another allocation from this FreeList will give back the address A.